Isaac T. Pease is one of the earliest inventors of spirit communication devices, and indeed his work seems to have predated even Wagner's first talking board patent. Born in Longmeadow, Massachusetts in 1809, Pease later relocated to Thompsonville, Connecticut, where he owned a successful woolmill. In the 1830s, Isaac Pease began manufacturing clock cases in his wood shop, purchasing the mechanical movements from firms like Terry and Hoadley, installing them in his finely carved cases.

These clock-crafting skills would be put to good use in the early 1850s, as the wave of Spiritualism swept across America and rapping mediums in the style of the Fox Sisters suddenly discovered their talents in towns and cities everywhere. Inspired by dial telegraphs that were prominent in the 1840s and 1850s, Pease had the idea of constructing a similar sort of dial face, with an alphabet, numerals, and some simple responses to questions marked around its perimeter. A central hand pointed, clock-like, to these various letters and phrases around the stamped-tin face, making his "Spiritual Telegraph Dial" the world's first "dial plate" planchette.

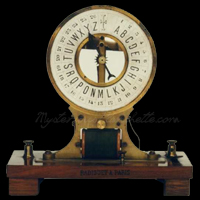

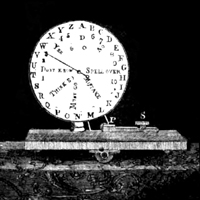

The only known surviving example of a Pease dial is somewhat problematic as a type specimen. It is part of a device built by Dr. Robert Hare as part of his "Spiritoscope" collection, and is a cast iron copy of a Pease dial plate. Furthermore, it is heavily modified and annotated from the original, with many of its original messages abbreviated or removed altogether. Hare's descriptions describe his Pease dial plates as containing many more elements than our nearby illustration, including the perimeter alphabet, and the phrases Yes, Doubtful, No, Don't Know, I Think So, A Mistake, I'll Spell It Over, A Message, Done, I'll Come Again, Good-Bye, and I Must Leave-all spreading out radially from the dial's center with the digits 0-9 spaced between them. Furthermore, it seems the dial was even more crowded, as Hare describes a series of 5 concentric rings on the faceplate meant for spiritual music tablature. Hare also confirms the existence of an instruction label on the back of the dial that explains the use of this tablature, and also reaffirms that these devices were made by Pease for at least limited commercial distribution.

The exact operation of Pease's dial plate is still unknown. Original accounts indicate that Pease's dial had no movement mechanism beyond the free-moving clock hand, and that it was the job of nearby spirits to move it: "A moveable hand, or pointer, is fixed in the center, and when a ghost wants to communicate with its pupils and friends in the body, all that is requisite is for it to give a gentle twitch to the pointer, and the revelation is accomplished." The 1854 article goes further, assuming a somewhat dubious tone: "Some Yankee ought next to invent a visible ghost and take out a patent." But Isaac Pease's own words dispute this manner of operation, as he stated in an article from that year: "with a good tipping medium to facilitate the movements of the pointer by agitating the table, letters will be indicated to the dial as fast as an amanuensis can write it down." We're not sure what the phrase "agitating the table" means, or if the medium is involved in actually "tipping" the device, though this may also be a "table tipping" reference. It could be the case that the pointer was free-moving, and the dial plate was held in the hands and tilted, so as to have the loose pointer fall on the desired letter.

But, again, Robert Hare's description throws us for a loop. In his book, he describes a Pease dial in its unmodified state before he dismantled them for his own Spiritoscopes, and he seems to indicate that the movement mechanism was much more complicated, befitting a clockmaker's art:

"The apparatus of the Pease above described...operates by means of a string extending from the brass ring in which the pulley string terminates externally to a weight situated upon the floor, so as to be taunt when at rest. Tilting the table...causes the weight to pull the string...to induce the revolution of the pulley, its pivot, and corresponding index."

From this description, it seems the Pease operated on a counterweight system, and that mechanism, given Pease's own description of manipulations of the device by mediums, seems most likely. Only time-and rediscovery of other specimens-will reveal the true nature of the device. Keep your eyes peeled and let us know if you spot something matching this description!