Kirby & Company are often credited as the first commercial producers of planchettes in the United States. However, recently-discovered accounts of the Spiritualist Robert Dale Owen actually confirm that the publisher G.W Cottrell, manufacturer of the Boston Planchette, actually had Kirby's company beat by a few years. There is no doubt, however, that Kirby & Co. successfully rode the wave in what would become The First Great Craze in the planchette's popularity, and offered the finest variety of the boards available then or later.

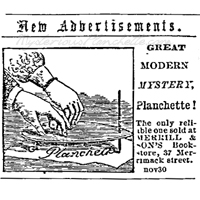

Research into the man behind Kirby & Company is still ongoing, but we do know from advertisements in New York papers of the day that he was a bookseller and games manufacturer -like most planchette makers of the day -operating a stationary shop at 633 Broadway. The earliest known ad for the company is dated 1852, advertising a game known as "The Kings & the Cavaliers." By 1868, the company seemed to cater to a more refined clientele, offering any number of items that represented the height Continental fashion.

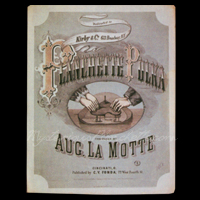

Kirby's offerings included Pinaud's Violetine, an exotic soap readily touted as the same used on French steamliners, personalized and embroidered port-monnaies (the company's fancy parlance for pocketbooks), chatelaines (expensive status symbols for high-society housewives that included decorative scissors, thimbles, and other household tools designed to be worn dangling at the waist), and the new Silver Chimes game, a croquet-like game with several versions that could be played indoors or out. The refined language and flowery promises of the company's advertisements leave little doubt that Kirby intended to cater to those of high-society, and by 1868, that same society with its Euro-centric mindset embraced the planchette, which Kirby & Co. were quick to offer. They quickly dominated the market, and composer August la Motte even dedicated the sheet music for his Planchette Polka to the company's rising star.

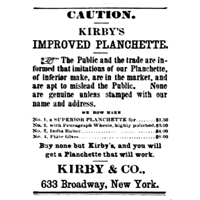

Kirby & Co Ad detailing Models Nos. 1-4. No. 0 is conspicuously missing, and was most likely a later economy model addition to the line

Due to their upscale clientele, among which fashion spread like wildfire, it may be that Kirby & Co is itself responsible for the surge in popularity of the device, even if the firm was not the first to introduce the enigmatic plank to New England's shores. On December 12, 1868, Kirby reported to an inquisitive reporter from the Round Table newspaper that he had already sold over 200,000 of the items, though it is, of course, impossible to verify this claim.

The planchettes themselves are among the finest ever produced. We know from advertisements that 4 models were initially offered, with another economy model possibly added later. This basic model was made of mahogany, sold for $1,and was known as the No. 0. Next in line was the $1.50 No. 1, which Kirby marketed as a superior planchette with a new patent wheel, with a board made of ash rather than mahogany. Apparently a good coat of varnish was worth twice that, because the highly-polished No. 2 with a pentagraph wheel sold for $3.00. These three boards are difficult to distinguish, not in the least because the vaguely touted features and the differences between them are tough to interpret. Of the surviving known examples, our best forensic analysis tells us that the infamous Longfellow Kirby, in the toy collection of the Longfellow National Historic Site is most likely a No. 1, or possible a No. 0, given that it possesses relatively basic economy style-castors most closely akin to those used on antique writing pentagraphs, with wheels of bone. The varnish doesn't look much of a cut above a basic splashcoat, but we'll give this old girl a break considering all she's been through with ol' Henry Wadsworth's family.

The Kirby plank in the collection of the Museum of Talking Boards is obviously a step above the Longfellow Kirby in terms of quality, and is most likely a No. 2 model. Its castors have a fine, detailed casting, thicker wooden wheels, and nice intricate flourishes. As we discover more planchettes, the more we'll be able to compare the various models and decipher their model designations.

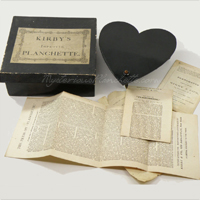

The final two boards rank among the most interesting and compelling specimens of planchettes ever produced, and Kirby advertised as such even at the time. The so-called No. 3 was touted as a non-conducting planchette and as the best planchette made, and was made of India Rubber -in this case most likely vulcanized ebonite, which has more of a hard plastic consistency and often served as a substitute for ebony. The planchette sold for $4.00, and came in a thick cardboard box absolutely stuffed with trade circulars, instruction sheets, and sales flyers, as if the purchaser needed any more convincing! Many of these materials reprint, in whole or in part, the 1867 "Once a Week" article, the first of many companies to use these materials in their planchette promotions. This is one amazing planchette, constructed entirely of plastic, with intricate castors in a similar style to Kirby's other models. It is absolutely and remarkably ahead of its time.

By 1869 a new addition was added to the line, and was so ingenious that it is a wonder that not all planchettes were thereafter made in its image. The No. 4, first revealed in the American Phrenological Journal, was made of plate glass. This, of course, enabled users to actually see what they were writing while they were writing it, though as brilliant as the idea seems, the brittleness and heft of the glass, combined with the staggeringly-high price of $8.00, which is equivalent to $130 in today's dollars, made this a rare and expensive commodity even in its time. All models of Kirby & Company planchettes were available at pharmacies, toy stores, and booksellers, where, Kirby claimed, they sold immediately. If only we could step back in time!

The castors of the glass Kirby represent an even further refinement of Kirby's earlier designs, and the high-quality turned brass continues to be reminiscent of castor designs taken from pentagraphs of the era -and they very well may be. One new feature that seems to have first shown up on the 'India Rubber' model is a small adjustment screw. Not only does this allow the wheel casings to be removed entirely, but they also allow the user to adjust the tightness of the castors, for better or more restrictive movement -not unlike a modern computer user adjusting their mouse cursor speed. This fine-tuning feature, combined with the transparency of the device itself, really does represent the pinnacle of planchette development, and users were undoubtedly thrilled with the results of the item, assuming its heavy weight was not too much to bear on the fragile pencils of the day.

Recently, our curator Brandon Hodge discovered a very special planchette in the collections of the Missouri History Museum of St. Louis, with some intriguing hints that it may have ties to the very man responsible for bringing planchettes to American shores: Robert Dale Owen. After months of investigation and prodding for the item's retrieval from the museum's archives, we can now confirm that the collection does, in fact, contain a Kirby planchette that once belonged to Robert Dale Owen. The archives include many of the personal effects of famed portrait artist Matthew Wilson -this planchette among them. The artist, a British immigrant who came to America in 1832, was a successful portrait artist who not only painted Robert Owen, but also captured the last portrait of Abraham Lincoln from life, just two weeks prior to his assassination. This find, with its association to the famous artist and its connection to Mr. Owen, is an incredibly exciting find and a real piece of American history.

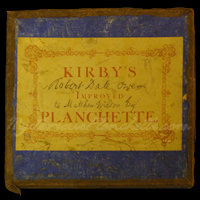

The box provides the most direct proof of the planchette's provenance. Not only is it signed in dedication to "Matthew Wilson, Esq." but Robert Dale Owen himself signed planchette himself, leaving no doubt that the item was a gift from the politician and reformer, though it would have come at a much later date than his portrait sitting, which was done in 1865 -three years prior to the planchette's production by Kirby. The box differs greatly from other existing specimens. It is bright blue, rather than the glossy black usually seen, and brown tape applied at some time long-past strengthens the box's borders.The inside would have contained the requisite fliers and instructional booklet, along with the pencil that can still be seen wedged in the planchette's aperture, as seen below. A bright yellow label with red ink is emblazoned on the front, and one can only surmise what an attractive package the planchette would have been as it sat on the bookseller's shelves awaiting purchase.

The Matthew Wilson planchette, gift from Robert Dale Owen. Collection of Missouri History Museum, St. Louis

The planchette itself is a fine quality specimen, and well-preserved thanks to the survival of its box. Now that we've secured photographs of the item, we are positive we've found the missing link in the Kirby line of planchettes, and its relatively simple castors leave little doubt that this specimen is a "No. 0" model, which would have run Mr. Owen a solid $1. Its label, like others in the wood Kirby line, is bright yellow, though unlike the box sports black in, rather than red ink. Like other wooden specimens, it has mahogany wheels, and in general has the classic, fine lines of all the wooden Kirby models. Of course, it does beg the question of why Mr. Owen, himself responsible for the planchette's original American manufacture by his friend G.W. Cottrell in 1860, would give the gift of a Kirby, rather than a Boston planchette. As we can see above, Kirby certainly dominated the market, and as they were higher quality boards, we can hardly blame him. But mostly, we're just thrilled to have made this discovery!

Do you own a Kirby? We'd love to see it! Contact Us!