Planchettes might have forever languished as a minor curiosity, were it not for a late-1867 article published in England's "Once a Week" periodical. This sensational 6-page story told of the writer's first encounter with a planchette, allegedly brought to the North of Scotland from American shores. Miraculous revelations received from multiple sittings with the device were recounted in great detail, and several illustrations accompanied the piece. The article generated immediate interest in the "new" devices, after years of confinement to a backwater cottage industry. Letters poured in demanding to know where the items could be purchased, and the public's interest was immediately piqued.

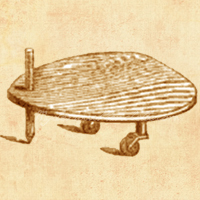

The first known planchette drawing, from October 26, 1867 "Once a Week" article. Oddly, the engraving shows a traditionally British form while supposedly depicting an American plank.

The illustrations do pose somewhat of a problem for researchers. It is unusual that the article's pictured planchette is distinctly British in form, with a round nose and flat back, and not the more traditional heart-shape of American planchettes, or even Cottrell's Boston Planchette. It may be the first 50 produced by Cottrell in Gardner's account were copies of a round-nosed British model; possibly Thomas Welton's. Whatever the case, the account caused quite a stir, especially considering the new era of cooperative media that meant it was not only immediately reprinted by newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic, but the numerous planchette manufacturers that sprang up seemingly overnight reprinted the article in full or used snippets from it in trade circulars, continuing to do so well into the 1920s. It must have been effective. By the following year, word of planchettes spread, and 1868 marks the "First Great Craze" of talking boards.

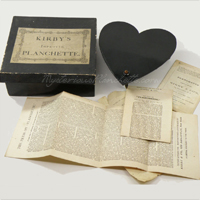

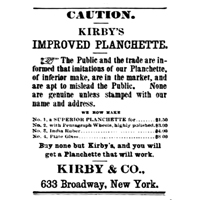

An explosion of planchettes came in the wake of the article and its subsequent reprints. Manufacturers like Kirby & Co, Gilman Moulton, and N. Bangs Williams tried to assert themselves as preeminent and "original" suppliers of the devices in America, while G.W. Cottrell struggled to maintain superiority that his firm held for years when interest was low. Everyone, everywhere, it seems, was experimenting with planchettes, and buying them in droves. Research turns up hundreds of newspaper advertisements for the year 1868, and Kirby claimed to have sold some 200,000 planchettes before the year was out, though it is, of course, immposible to validate this account.

An 1868 Kirby Ad showing their wide array of planchettes and warning customers of imitators, of which there were many.

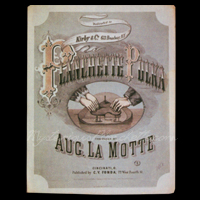

A similar explosion occurred in Great Britain, though the English would make planchettes more distinctly their own with The Second Wave of popularity as the new century approached. In the meantime, makers like Thomas Welton (who claimed to have sold precisely 1,466 boards before the 1868 craze) going into damage-control mode to assert the superiority and originality of his products and lay singular claim to the suddenly popular phenomena, while big-time toymakers like George Bussey and Jaques & Son eyed the potentially lucrative possibilities of catering to the fad. Books on the subject suddenly sprang up on both continents, from Kate Field's "Planchette's Diary" pamphlet in 1868, said to be written entirely through the planchette itself, to popular writer Epes Sargent's "Planchette, or, the Despair of Science" in 1869, which sought to furnish a detailed history of the phenomenon, though ignored details of its earliest days and Cottrell's involvement, giving first American credit to Kirby instead.

Back were the days when table-tipping took entire nations by storm, only smaller talking tables in the form of planchettes dominated these late-1860s households. With the American Civil War finally over, a new public consciousness spread as survivors turned toward the promise of Spiritualism to deal with the staggering loss of lives caused by the war. This cycle would drive similar revivals in subsequent years. Buyers of planchettes were promised they could explore the exciting new spirit communication possibilities in the privacy of their own homes, and not rely on potentially fraudulent mediums that were by this time being continuously debunked by a press hungry for sensational journalism in the absence of battle.

Each new company seemed to offer a new design or an improvement on an old one. Kirby & Company began with wood planks, but soon offered up plate glass and even India rubber models. Holmes & Company not only produced planchettes, but revived the dial plate ideas of Isaac Pease with alphabet boards that incorporated rotating disks as pointers. Toy and game manufacturers finally started to cash in on the devices' popularity, nudging the stationers and booksellers who dominated the early market aside to establish their own brands with beautifully-lithographed boxes that often concealed less-than-serviceable trinkets within. It was a grand era of experimentation and evolution for the devices, and indeed it golden years.

There were other refinements. Ralph Jennings filed the first true planchette patent, with an unusual shape and beanie-style propeller as an "improvement." Bizarre attachments meant to insulate or charge the device with spiritual energy appeared, such as with Bangs William's bizarrely beautiful planks and their cast-metal "insulators." Gilman Moulton followed suit with an alternating set of copper and nickel plates on his board's topside, meant to serve as a primitive battery. Manufacturers toyed with castor design and board shape, with each seeking to outdo the other with outrageous claims of one wood being more suited to spirit communication than another, or the lack of competitor's insulated castors making their products inferior. Copycats were common, too, making modern identification of many planks difficult given the clandestine nature of the manufacturers.

But after the sensational accounts,untold sales, and even popular songs, experimentation with spirit communication by the public declined for a time. The 1870s were a period of consolidation for Spiritualists as they sought to establish as a legitimate religion. Several attempts were made at a national organization and cohesive belief, something hard for a group who had so many claimants with spirits supposedly telling them the true nature of the afterlife. Contradictions abounded, as did a plethora of deceased luminaries who began showing up at seances to guide believers toward the true path, including Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, though often with suddenly horrendous diction, spelling, and grammar that the luminaries hardly possessed in life. Mumler was tried for fraud due to his fake "spirit photographs" and found guilty. The public began to recoil ever-so-slightly from any talk of spirits or their messages, and turned its attention to other, more material, matters.

An 1896 example of planchette spirit writing. The full text reads: "The attitude of convicted believers in Spiritual life toward the blind leaders of the blindly dogmatic in Spiritual matters should be that of the Seers to those yet in the dark, as full of lovingness and tenderness as one who sees to those bereft of sight."

Thus was the First Great Craze of planchettes. As the 1860s gave way to the 1870s, the popularity of the fad had declined as well, and by the 1880s few of the original stationers and booksellers producing and offering the devices remained. The early rapping mediums who had been able to withstand scientific scrutiny were forced compete with upstart, low-rent mediums less practiced and more prone to exposure. All were also forced to deliver exponentially more sensational results in their sittings, with apports and materializations becoming more common. As they pushed the boundaries of what a skeptical public was willing to accept, the media turned against them with a renewed vigor, reporting with glee every exposure and doubt, which grew more enthusiastic as time wore on.

Whether these exposures dampened planchette sales is anyone's guess, though decline they did, at least for a period. Of course, planchettes and Spiritualism were always sympathetic cousins, thought Spiritualists rarely subscribed to the tools than those with a more leisurely interest in spirit communication, and rare indeed are those who publicly claimed use either of planchettes or their successor, the ouija board. But new innovations were ever on the horizon, and for those who continued to refine and innovate the tools of spirit communication in the background of this decline, a Second Coming awaited.