With the new century, Spiritualism was increasingly less likely to be associated with talking boards as it had been in the past. It was now formally a religion, with dwindling adherents, aggressive detractors, and a spate of high-profile exposes that only got worse as such prominent personalities as the magicians Dunniger and Harry Houdini joined the fray in the 1920s. With such negative attention, the public increasingly dismissed the movement, and adherents internalized their activities. But due to the overwhelming commercialism of Ouija boards by William Fuld in the early part of the century, the public was more willing to accept the curiousness of the devices on their own unusual merits in a return to their parlor entertainment roots, rather than as a subscription to any formal doctrine promoted by Modern Spiritualism.

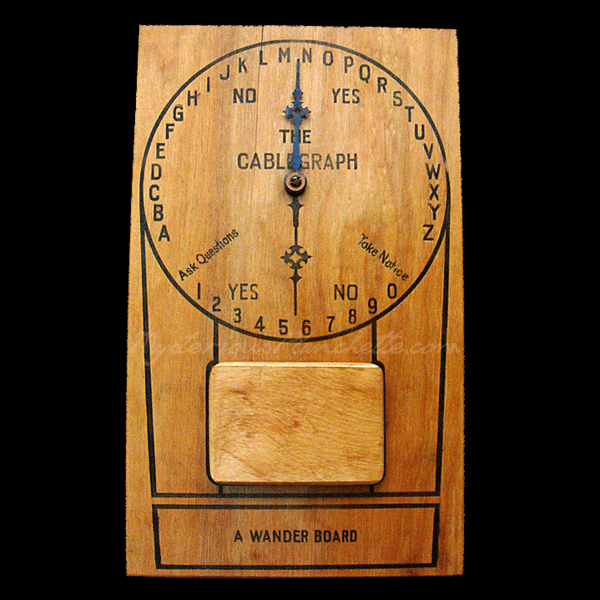

American planchettes of this period tended to flare briefly on the marketplace before fading into obscurity, or exist only as fascinating patents. Rather than the "Third Great Craze," we might call this period the "Last Desperate Gasp" for American planks. The beautiful "Psycho" board was its namesake company's flagship product, but as it was introduced just as the Great War was underway, it failed to gain traction or attention. The patented Jenness "Mystic Artist" similarly failed, though it tried to cater to some New Age-precursor movement along the West Coast in the 1920s. George Pearson refined his earlier "Cablegraph" with a new design that mostly did away with the earlier horsehoe shape, and protected his improvement with a new patent.

George Pearson's refined 'Cablegraph' as improved in his 1919 patent

Photo courtesy Museum of Talking Boards.

Things were much more promising with British planchettes in England, where Elijah Bond had failed to establish firm footing for talking boards in the 1892. Rather, planchettes found new life here, and as the Great War came to a close, planchettes from a wide variety of manufacturers flooded the markets. As they had years previously, toy companies and game manufacturers were the dominant providers of writing boards, and firms such as Jaques & Sons, Chad Valley, and H.P. Gibson & Sons all produced planchettes at a prodigious rate to keep up with post-wartime demand.

The British planchettes of the 1920s and 1930s vary in quality, from the incredibly serviceable and high-quality planks from scientific instrument makers Weyers Bros, to some of the rather dinky-if sometimes stylish-offerings of Chad Valley. On one hand, the toy makers were making what they largely considered toys, not serious tools of spirit communication, though this did not stop some firms from producing quality products that competed with the best planks ever offered.

Sadly, even with their popularity in Great Britain, planchette sales eventually plummeted, especially in competition with talking boards in America, where users could see their messages spelled out rather than having to interpret badly-scrawled cooperative spirit writing. By the close of World War II, ouija boards and their ilk would experience the expected upsurge in sales in popularity, but this time planchettes would not join them. In the eyes of the consumer, the days of automatic writing were over, and planchettes had evolved into nothing more than the pointer for more popular talking boards. Like the patent surge of the 1920s, intervening decades brought new innovations and changes to spirit communication devices in the form of dozens of new patents for dial plates, talking boards, and other fortune-telling devices, but the days of the automatic writer were over.

After WWII, talking boards of all shapes and sizes totally dominated the spirit communication market, though a wild assortment of new pointers for the boards would serve as a fitting reminder of their larger ancestors, though now reduced in form and devoid of the pencils that had for decades scribbled messages to curious users. True writing planchettes would from here on out only be offered by the occasional New Age bookstore or esoteric concern, such as those by Venture Bookshop in the 1960s, the Metaphysical Research Group in the 1970s, or Sorcerer's Apprentice in the 1980s. The good news for collectors is this: like a good band who finally announces their breakup, we now know exactly what has been put out into the world to collect, like so many fantastic albums, and now we just have to figure out where to look!