After planchette's First Great Craze of the late 1860s, the devices suffered a sharp decline in the 1870s. Bangs Williams went bankrupt after gambling his fortunes on Wall Street. Kirby & Co., G.W. Cottrell, and other stationers returned to the book trade in the absence of strong planchette sales. Some evidence suggests Selchow & Righter did introduce their "Scientific Planchette" as early as 1875, although manufacture of that model persisted well into the 20th century. For the most part, however, scientific explanation began to intrude on parlor entertainment, and exposes on the devices such as "The Three-Legged Imposter" or "Confessions of a Reformed Planchettist" perhaps dampened the enthusiasm of the public's penchant for tabletop spirit communication. Spirit photographers like William Mumler, who had once offered hope of the persistence of the soul with spirit photographs showing the ghostly faces of the deceased, now faced huge public controversies and high-profile charges of fraud. Just as media reports fanned the initial flames of popularity with multiple reprints of articles extolling the virtues of the planchette, so too did they enthusiastically drench the fires of the fad in subsequent years with withering editorials.

There is a distinct lack of patent applications for spirit communication devices in the 1870s, and the public's attention was, for a time, apathetic toward Spiritualism, but not all hope was lost. Occasional sensational stories of the little board's predictions bolstered interest and helped stave off the device's media-provoked death knell. In one instance, an 1876 account in the American Spiritual Magazine told of the "easiest means of intercourse" with a report of a family communicating with their son through an alphabet-painted table and a rod-shaped planchette, giving us a reminder not only of where spirit communication started, but also a look ahead toward true talking boards. Another account told of treasure seekers using the planchette in an attempt to reveal the gravesite of an Indian chief buried with a fortune in jewelry.

Physical mediums such as Mme. d'Esperance, Madame Guppy, and the Eddy Brothers were on the rise during this period, and provided increasingly sensational and miraculous materializations of spirit guides and ghosts in seances on both shores. Madame Blavatsky combined Spiritualist thought with eastern mysticism and founded the popular Theosophical Movement. Katie King's full-body materializations in England and their study by prominent chemist and physicist Sir William Crookes kept spirit communication in the public eye. Spiritualism again attempted to establish formality as a religion with a national conference, though it failed, and personalities such as William Stainton Moses and Emma Hardinge Britten came to the fore to give the movement leadership, promoting its virtues through lecture tours both at home and abroad. There was also a sudden surge in topical periodicals sympathetic to the movement. Furthermore, the Society for Physical Research formed in London in 1882, and provided a somewhat approachable, populist format for investigations of spiritual and psychic phenomena with the goal of educating the public on the things they were hearing about and perhaps witnessing.

After the lull of the 1870s, the 1880s finally bring with them the bright promise of new innovations in spirit communications tools. Perhaps the laborious task of deciphering scribbled spirit writing grew wearisome, but advancements in the form of planchettes began to incorporate their own alphabets, rather than relying on the scrawled notes left behind by the item's erratic pencil. The Becker and Ballatine dial plates were patented, but it is unknown if they were ever produced on a large scale, if at all. A new breed of enthusiastic spirit communicators erupted. Hudson Tuttle not only published book after book, but developed his "Psychograph" dial plate based on the earlier Holmes model, and apparently did quite well selling the device from his Ohio home.

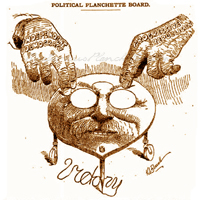

An 1886 depiction of the "talking board" which would inspire Charles Kennard to pursue production of the Ouija board.

Apathy toward home-based spirit communication faded, and it slowly came again in to fashion. By 1886, Spiritualist circles in Ohio had abandoned planchettes altogether, and illustrated news reports trumpeted the "The New Planchette," proclaiming the early demise of their precursors with the proclamation that "planchette is simply nowhere compared with the new scheme for mysterious communication that is being used out in Ohio." The article went on to describe what we know as talking boards, and the article was reprinted many times over. While the effect was not immediate, news of this innovation would reach ambitious ears, and from the germ of this idea a new era of spirit communication devices would bloom. With this innovation, planchettes would not only undergo a revival, but ultimately be resigned to their ultimate fate-not as independent devices unto themselves, but accessories for the new talking boards.

Another 1886 depiction of the "talking board," soon to signal both the revival and the death knell of writing planchettes.

Though the details of the talking board's origins have been clouded by time and deliberate misinformation by those seeking to claim rightful entitlement to the board's creation, we know that publication of the 1886 article soon reached the ears of Charles Kennard, a fertilizer salesman, and E.C. Reiche, a cabinetmaker, both living in Chestertown, Maryland. Both seem to have toyed with the idea, with Reiche apparently making several of the boards that were played with at a community party, and with Kennard later claiming he brainstormed the idea on his kitchen table with a breadboard and a saucer. Whatever the case may be, Kennard moved to Baltimore, Maryland in 1890, bringing the idea with him, where he eventually partnered with several Mason brethren to patent and market the device as the Ouija Board. The world of spirit communication tools would never be the same.

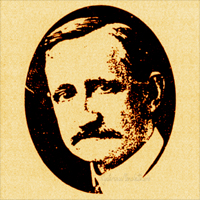

Charles Kennard, who brought the talking board concept to Baltimore and reversed the fortunes of spirit communication devices.

The explosion in popularity in talking boards at this time cannot be overstated, and was well above-par with the First Great Craze of planchettes in the late-1860s. Kennard's own Kennard Novelty Company, as well as its subsequent incarnations run by William Fuld and others, spawned a multitude of imitators in subsequent years; something still happening to this day. Luckily for planchette enthusiasts, the rise of talking boards took planchettes with them. Though early planchette forms had been demoted to mere pointers with the new device-especially with Kennard's drastically-changed "paddle" planchette design-the Ouija's popularity resulted in a new interest in writing planchettes from manufacturers wishing to take the plunge into spirit communicators without running afoul of the protective, and very litigious, makers of the original Ouija.

An original Kennard "Paddle" Planchette, designed to differentiate his new Ouija board from previous planchette incarnations.

Meanwhile, a new age had dawned in industry. No longer were stationers and booksellers the dominate providers. Instead, Milton Bradley's successes in the 1860s had spawned an entirely new industry and infrastructure to produce board games, and game and toy manufacturers stepped forward as the primary makers of planchettes. Innovations the likes of which were previously unheard were suddenly everywhere, with endless variations of talking tables both popular and obscure competing for a share of the thriving market for the devices.

George Pearson's "Cablegraph" is a perfect illustration of the ingenuity of the new era of talking boards.

Alison Ruff-Genegels Collection.

In American, dominate companies such as Selchow & Righter and J.H. Singer produced classically-American, heart-shaped planchettes. E.I. Horsman offered not only a "Scientific Planchette" from the same "jobber" as Selchow, but also the "Daestu"-a wooden framework meant to suspend the wrist in a brass pan to facilitate spirit writing. Milton Bradley even entered the fray with the slide rule-like "Genii" board, that was either a copy of, or copied by, the Aura Psychic Board. George Pearson produced perhaps some of the highest quality devices known with his patented Cablegraph Wander Board, and would continue to make them right up into the 1920s. It was indeed a new dawn for the devices.

Among the finest of British planks, Jaques & Sons produced quality planchettes throughout this era and into the next.

In Great Britain, the heavyweights of the English toy industry clashed, perhaps trying to make up for their failure to properly capitalize in the fad two decades previously. George C. Bussey & Company, giant providers of airguns, croquet, and other sporting goods, may have offered their fine quality planks during this period, made from the same willow-wood as their popular cricket bats. Jaques & Sons likewise offered an array of high-quality boards built on the classic British design first established by Elliott Bros. and Thomas Welton, of such workmanship it threatened to put their American cousins to shame. F.H. Ayres also produced not only a distinctive and quality plank, but also invented the Pytho dial plate and the Chrao automatic writer, both held to the same high standard as the company's other products.

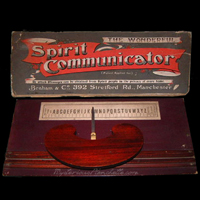

A W.T. Braham "Wonderful Spirit Communicator" from the 1900s, later repackaged by Two Worlds Publishing.

Spiritualists had long eschewed the use of such pedestrian, commonplace tools, instead relying on mediums to produce spirit phenomena. But Two Worlds Publishing, publisher of the leading English Spiritualist newspaper of the era, commercialized the tools in a major first for followers of the religion. Headed by prominent Spiritualist Emma Hardinge Britten, the company developed and produced beautiful lateral-movement dial plates, built on boardmember W.T. Braham's models, known as "Telepathic Spirit Communicators." These items were offered alongside other tools such as crystal balls, as well as traditional planchettes with ball-bearing castors of the highest quality.

Planchettes road the coattails of talking boards to success in the early years of the 20th century, but soon the Great War loomed, and such accoutrements again took a back seat in the face of an international crisis. In America, this era would be the last great craze of planchettes, with talking boards almost totally taking over from this period onward, regulating the wonderful autowriters to a mere, oft-ignored pointer for talking boards. In Great Britain, however, talking boards failed to connect after original Ouija-patentee Elijah Bond's disastrous trip to establish a foothold for the items in that country, giving planchettes one last great gasp of popularity in a Waning Age before consigning themselves to the dustbin of history.