Hudson Tuttle is one of the most fascinating personages of the Spiritualist movement. Born October 4, 1836 in Berlin Heights, Ohio, Tuttle was surrounded by the ardent religious fervor of that region. He became a skeptic of established religions at a young age when his prayers to God to mend a broken pitchfork-and spare him a beating by his father-went unanswered. Tuttle became involved in Spiritualism during the early stages of the movement, attending a seance hosted by a Congregational minister seeking to investigate the spirit knockings recently popularized by the Fox Sisters for himself. According to accounts, Tuttle entered a trance-like state and produced automatic writing, and spirit raps spontaneously erupted in his presence. So began his long association with his "spirit communicators" or "superior intelligences:" intangible entities who he claimed imparted fantastic knowledge in him.

The presence of these ghostly tutors might have explained much, for Tuttle claimed to have attended school only "eleven months in all," and yet the supposedly uneducated farm boy produced great volumes of written work in his lifetime. He credited all to his spiritual communicators. His published theories were espoused by F. C.L. Buchner, and no less a personage than Charles Darwin quoted Tuttle in The Descent of Man! His wife, Emma Rood Tuttle, was no less prolific, and was an accomplished composer, lecturer, childrens' lyceum promoter, and writer.

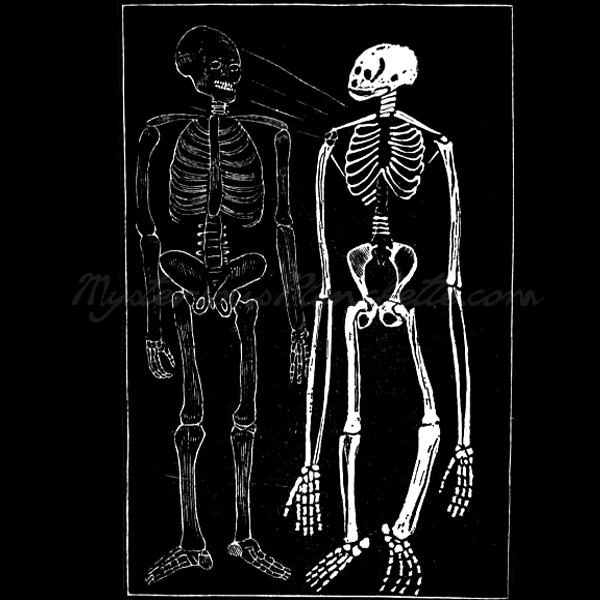

Tuttle's attempt at the evolution of whales, as recounted by his "superior intelligences" from Arcana of Nature, 1859

His penultimate work, entitled Arcana of Nature, was began when Tuttle was only 18, but his incorporeal tutors-among them the deceased French naturalist Lamarck and Alexander von Humboldt-supposedly commanded the first just-completed manuscript destroyed. They claimed it necessary to "weed out the imperfections" that the medium had introduced in his translation from the spirit world. Finally published in 1859, the book is a fascinating pseudo-scientific work written without the aid of a library, reference books, or even the benefits of an education, if Tuttle's claims are to be believed.

The work is no less than the attempt at the complete origins of man and the cosmos from astronomic, philosophic, and anthropologic viewpoints. It is amazing in its scope, and Tuttle even takes a stab at bizarre theories of evolutionary biology at a time before Darwin's On the Origin of Species, which would be published the same year. It does, at times, rely on crackpot theories popular at the time, such as phrenology and early eugenics, which can give some sections an overtly racist tone from a modern viewpoint. But the work is fascinating, if for no other reason that it came from the mind of Ohio horse breeder, but it still stands as an amazing testament to Hudson Tuttle's incredibly prolific life.

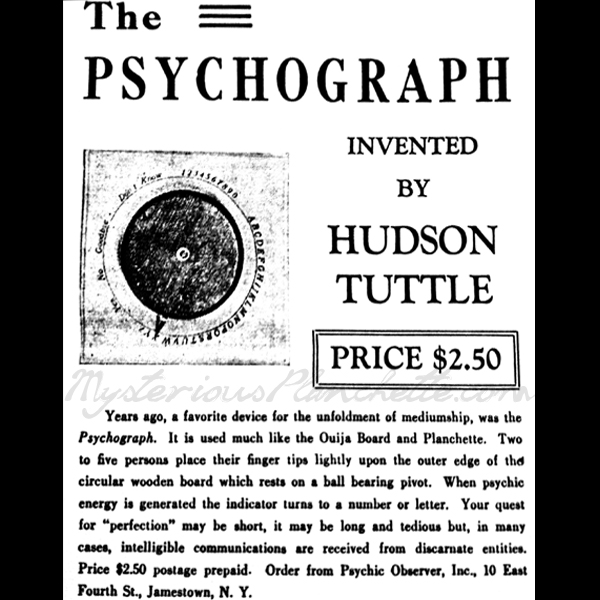

Some of Tuttle's other works include Scenes in the Spirit World in 1855 (later published in England under the title Life in Two Spheres), Mediumship and its Laws in 1890, and Stories from Beyond the Borderland in 1910, among many others. Two Worlds Publishing produced many of his books, including Arcana of Spiritualism in 1900, though Tuttle also ran his own publishing company from his Ohio home in later years, producing not only his books, but also his dial plate Psychograph.

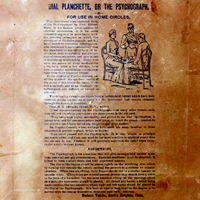

Another Psychograph, this one from collection of the Museum of Talking Boards. One of only four known to survive.

By the early 1880s, there was a shortage of options to writing planchettes. Wagner's own psychograph-patented but not likely manufactured-was decades gone. Isaac Pease's "Spirit Telegraph Dial" was another relic from 30 years previous. Dr. Robert Hare's experiments with his Spiritoscopes were remembered and even invoked in Tuttle's own invention's advertisements, but were never made on a commercial scale. And Becker's pointer board, patented in 1880, was on the right track, but doesn't seem to have ever been produced.

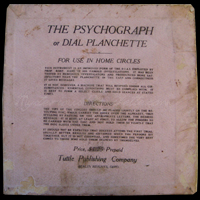

The back label of the Orlando Psychograph, somewhat less ornate than the Hodge specimen, most likely making it a slightly older model.

So it was that Tuttle stepped in to produce an inexpensive spirit communication tool as an alternative to the planchette, a bit ironic given his beginnings as an automatic writer. This device found form in his "Psychograph." First offered in the early 1880s, the board seems to have been quite a success on both sides of the Atlantic, with the veritable juggernaut of Two Worlds backing him in England, and his own reputation and name promoting the device in the States. It should be noted, however, that the form of the board closely resembles the Holmes Alphabetic Planchette available in the late 1860s, and given Tuttle's prominence and long tenure in the Spiritualist movement, it is unlikely he was unaware of the New York board.

The Psychograph is a 9-inch square of stout cardboard, covered in paper carefully glued and folded around the back corners. The frontpiece is printed with an intricate square border around a circular dial consisting of the alphabet, the numbers 0-9, and the phrases "Yes," "No," "Good Bye," and "Don't Know." A thick wooden post, about 2-inches in diameter, is glued to the board's center, and has a corrugated groove for retaining ball-bearings. A 5-inch circular wooden disk is screwed to the top of this, sandwiching the ball-bearings and allowing free rotation of the curved brass indicator that sprouts from the disk's bottom. The back paper covers the folds of the paper frontpiece, and its appearance differs in all 3 known examples, but all contain instructions of varying complexities.

Back label of later Tuttle Psychograph in Hodge Collection. Note new illustrations, endorsements, and a slight price drop.

Due to the dial plate's cardboard construction, few seem to have survived to the present day, and all 4 known survivors differ slightly in appearance. In the two examples we can directly compare, the wooden disk and central post are identical, though the front border's intricacy and dial's letter fonts differ. The way in which the paper is folded around the board's back is identical, however, though the instructions vary between relatively short, to long and ponderous, with endorsements from such luminaries as Captain D.B. Edwards and Dr. Eugene Crowell, with at least one nod to Professor Hare. The price varies from $1 to $1.25, and was sent postpaid from Tuttle's Berlin Heights address.

Hudson Tuttle took his Psychograph very seriously, as you can tell from the following explanation from the December 3, 1887 edition of the Religio-Philosophical Journal:

"The instrument is not a mere machine that will grind out communications; it is only a delicate means. It must be used intelligently. The sitter should sit with reverent seriousness, and undivided desire, and at fixed times, and not become discouraged if many sittings pass without results. There is scarcely a family in which at least one sensitive or mediumistic person may not be found, and the discovery of such sensitive members and their development, is the desirable office of the Psychograph. "

Collectors are faced with something of a conundrum in an advertisement discovered in a 1949 edition of the Psychic Observer magazine. The ad reveals that in that year, the magazine's publisher offered replicas of the Tuttle Psychograph for sale. It is unknown just how exact these replicas are, if they reproduced the back paper instructions exactly, or if they replaced the Tuttle address by branding them with the magazine's own moniker. All 4 surviving Psychographs carry Tuttle's address and original prices, and until one of these replica items is either discovered for comparison, or the extent of the company's reproduction uncovered, we have some lingering doubts as to dating and identifying these marvelous dial plates.

Hudson Tuttle died December 15, 1910, in the same town he was born: Berlin Heights, Ohio.